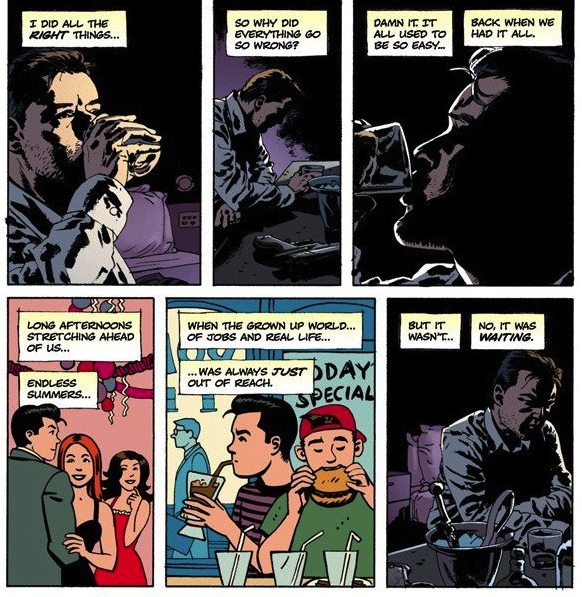

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about media that I personally adore but would never recommend to a friend. I’m re-reading the endlessly clever and disturbing Last of The Innocent by Ed Brubaker which is to this day one of my favorite graphic novels, but it also requires a near encyclopedic knowledge of and irrational nostalgia for Archie comics that is a barrier to entry for almost everyone I know. And even if they could find a way past that unfortunate pre-requisite, there’s also the fact that it’s a crime book.

Crime fiction, which I love dearly and is one of the genres that made me want to become a writer, falls firmly into this category of great fiction I will never recommend to anyone. I adore hardboiled crime stories, but it’s 2021 AD and that’s a really tough time to breathlessly tell a friend to go read or watch any media that ends with one or more of the central characters getting shot to death by the police. But unfortunately that’s how a fair majority of my favorite crime fiction ends.

I don’t intend to make some grand statement about policing in America in this piece, I think those points are made much more thoroughly and eloquently elsewhere. But I can’t imagine that anyone who has been paying attention to the news over the last several years is overly comfortable with narratives that prominently feature police violence, regardless of their personal political leanings.

What’s strange is that with this admittedly towering hurdle set aside for a moment, these stories don’t really smack of blue propaganda and are in many ways humanist case studies set in struggling communities. Good crime fiction ventures far beyond daring bank robberies and drug deals gone wrong and into the destruction and desperation wrought by generational poverty, class warfare, and systemic corruption and discrimination. Even if the good guys “win” in the end the reader is ultimately left with the vague sense that the society the heroes live in isn’t functioning anywhere near the way it was intended to, and the villains of the story are an obvious symptom of that perpetual state of disrepair rather than the cause.

This creates a curious fictional reality in which crime is very clearly a systemic problem wrought by vast inequality, not an individual one wrought by a dereliction of personal responsibility, and yet the only solution for it the narrator offers is state sponsored murder.

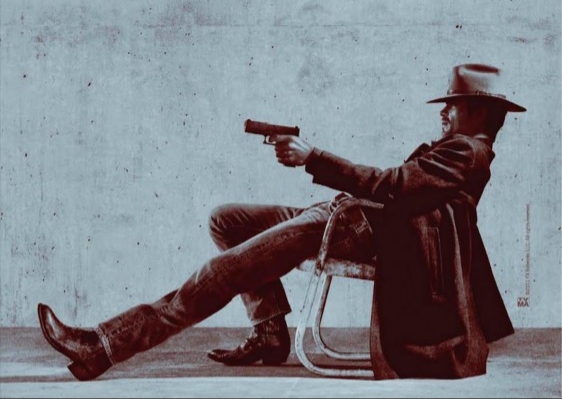

For example, Justified is a series based on the novels of Elmore Leonard and probably the most underrated crime television show of this century. Its title is derived directly from the term “justifiable homicide” which refers to killings police commit in the line of duty. It’s literally right there in the title.

The central narrative of Justified is focused on Harlan County in Kentucky, a region famous for being economically and geologically ravaged after the coal boom and subsequent bust. There are some colorful gangsters and sociopathic killers in Justified, but the vast majority of the criminals in the story are either hard up from years of famine, working tirelessly to prop up the tentpoles of their struggling communities through any means necessary, or trying to escape Harlan once and for all and find better prospects elsewhere. This depth of character and diversity of motivatons brings rich and welcome complexity to the story, but also makes it all the more disconcerting when the presumptive heroes of the story show up and pump bullets into them.

I think there are a lot of reasons why crime stories wind up like this: intelligent, progressive pieces of fiction that conclude like a 50’s educational film. Among other things it probably speaks to a crisis of conscience in an America that values strength and individualism as broad archetypes but often finds itself confused and frustrated when trying to apply them practically to modern issues.

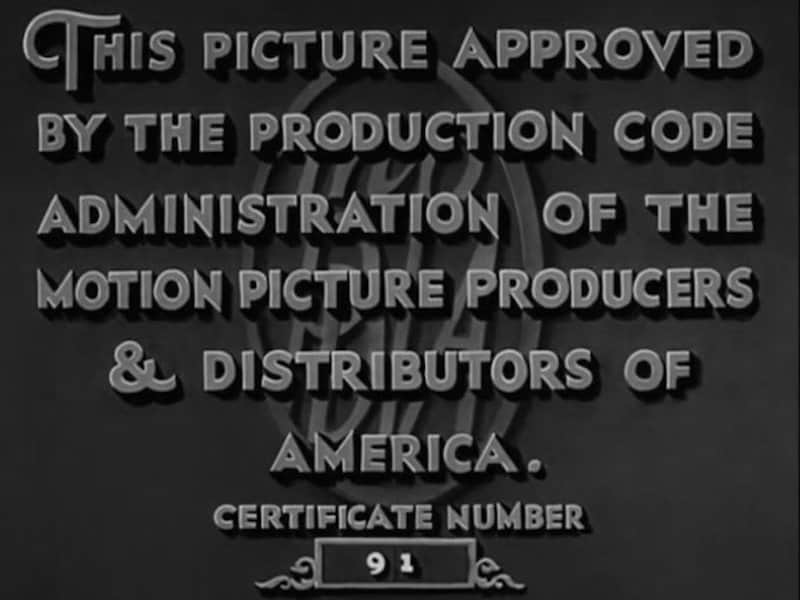

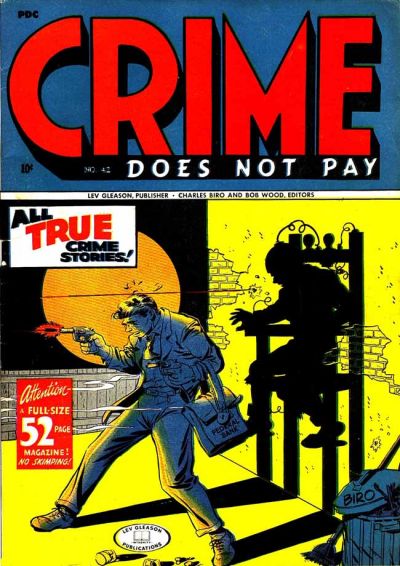

But I think the major factor is tradition. The heyday of crime fiction was the 1930’s and 40’s when depression era outlaws still grabbed headlines in a way that only mass shooters and TikTokers do now. But thanks in no small part to the Motion Picture Production Code of 1934, more colloquially known as the Hays code, these stories were largely confined to the narrative that crime is always a bad idea. In addition to banning things like onscreen mixed race couples and homosexuality, The Hays code both implicitly and explicitly stated that depictions humanizing or glorifying criminals were to be avoided at any cost.

This usually meant that criminal activity, even in the most famous crime films of the era, was largely limited to innuendo and that most films ended with criminals receiving some measure of comeuppance at the hands of authority just so creators could cover their bases and assure widespread distribution of their films.

The Hays code was relatively short lived and by the 70s filmmakers were diving back into all the sex and violence they had missed out on with aplomb. But, with a few notable exceptions, the endings proscribed by the Hays code seemed to endure in crime fiction. 1973’s Black Caesar is a wild exploitation crime film full of things that would have propelled the drafters of the Hays code onto their fainting couches almost immediately, but it still ends with Fred Williamson face down in an alley. Between Scarface, Carlito’s Way and Dog Day Afternoon Al Pacino probably just stopped bothering to wash the fake blood off himself as he traveled between sets. And modern films like The Departed and Uncut Gems certainly aren’t immune to the trope either.

Serialized police precinct and procedural shows are even worse in this regard as most of the stories are introduced and play out in their entirety within a single episode, which means that after a few seasons most of the detectives and hard-nosed beat cops we’re tuning in to see have body counts to their names that would make Jason Voorhees flinch.

There’s probably something to be said about the general nature of tragic storytelling at work here as well. But in Greek tragedies and other classic works, tragic heroes were doomed for flaunting morality and what the storytellers saw as immutable cosmic principles. The villains and anti-heroes of crime fiction are doomed merely for flaunting the authority of the society they live in, whether that society is just or not.

I think it’s more likely that for creators, despite their best efforts to do something original, a story doesn’t feel rooted in certain genres without retaining at least some of its tropes either earnestly or in parody. Slasher movies don’t feel right without a final girl, action movies can’t get by without killing a few family members as “motivation,” superhero movies can’t be about anything other than stopping a villain from collecting a series of glowing gems.

What’s remarkable about the tropes that crime fiction has held onto and what sets it apart from a lot of other genres in this respect is that these tropes were once determined by what was essentially the law.

This happens more often than you’d think, and sometimes it’s a good thing. Suspiria and Deep Red wouldn’t be nearly as ethereal and intriguing without the twice dubbed dialogue track, a holdover from Benito Mussolini’s ban on synchronized sound in films for propaganda purposes.

But in crime fiction it creates an odd dichotomy in which we are expected to take what is happening in front of us as a morality play despite the fact that manmade rules and conventional authority are lended a grace and dignity and cosmic importance they aren’t usually afforded in the real world, much less within the confines of fiction where typically all bets are off. While some crime stories are able to avoid the pitfalls of tradition and conformity, it feels like far too often my favorite ones do not.

It’s a weird fit for stories that are otherwise awash in existential themes and nihilism. It’s a bit like if in an alternate reality romantic comedies were essentially the same as they are now, but a significant amount of them ended with Reese Witherspoon being burned at the stake in the middle of town for promiscuity.

I don’t think there’s necessarily a problem with calling back to and relying on tropes in storytelling. But I do think it’s vitally important to consider why a trope came to exist in the first place, especially when it might be antithetical to the stories we’re trying to tell.