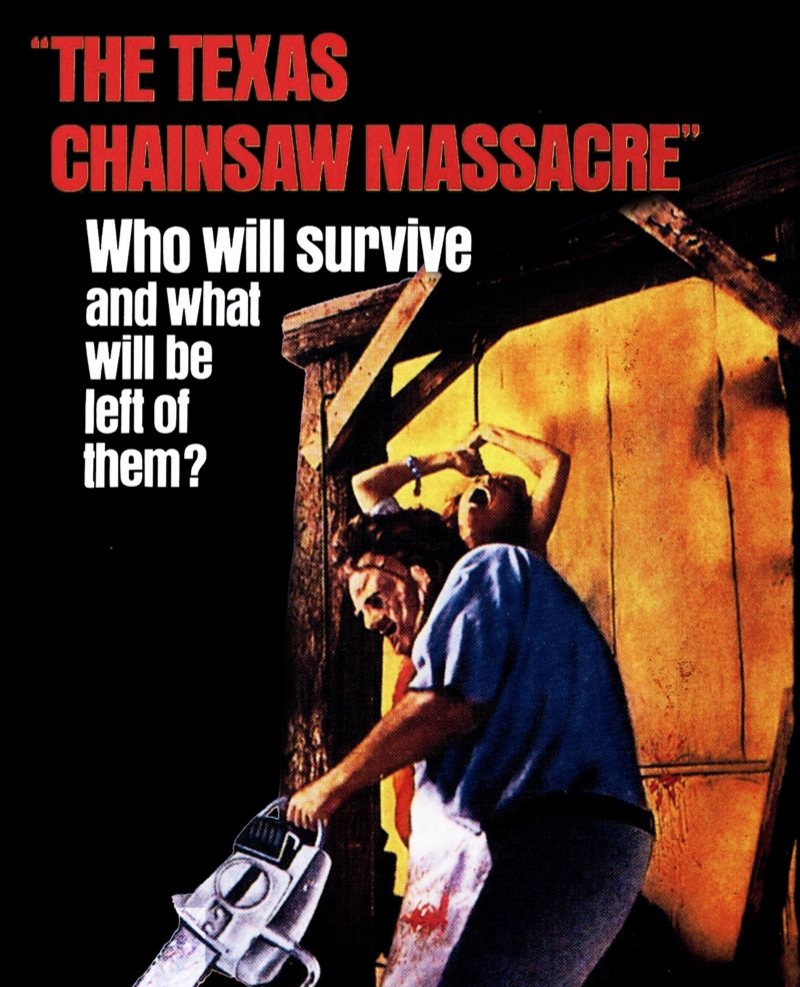

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is simultaneously the best and worst title for a movie. At the same time that it conjures something truly powerful in the mind of the viewer before the movie even starts, it also ensures that a fairly significant number of people who would likely appreciate it will never actually see it.

Tobe Hooper is a brilliant horror director but he never rose to the status of John Carpenter or Wes Craven, and I’ve always thought that could be at least somewhat attributed to the fact that even though A Nightmare on Elm Street and Halloween are both much more violent and explicit than The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, their titles rest a lot more comfortably atop a theater marquee than the latter. In addition to that simple aesthetic difference, there’s also the fact that Halloween and Nightmare feature archetypal, almost cartoonish villains, whereas most of the villains in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre are merely gruesome caricatures of regular people.

Growing up in a liberal household, and already fairly inoculated to the lurid nature of horror films, the most evocative word in that title for me was never “Chainsaw” or even “Massacre” but “Texas.” Texas, the deep red state, home of George W. Bush, America’s 43rd president and the chief antagonist of the young, left leaning counterculture for most of my childhood. I’ve obviously met a great number of wonderfully charming and ideologically diverse Texans now that I’m a little older, but back then my view of the state was, and in many ways still is, colored unfairly by the voting percentages that bore out over the election nights of my youth. Of course the images that came to mind when I heard the word Texas were precisely what Tobe Hooper, a proud native Texan peddling his bizarre black comedy in markets from Los Angeles to New York City, was hoping for.

The film premiered in fall of 1974, just two years removed from the night the storied southern and middle American voting block Ronald Reagan would later dub the silent majority, an evocative moniker that rivals The Texas Chainsaw Massacre both in terms of its simplicity and its foreboding implications, carried Richard M. Nixon to what is still the widest margin of victory in an election since World War 2. It was coincidentally also the first time in over 16 years that a Republican candidate had won Texas in a general presidential election, starting a trend of sweeping Republican victories in the lonestar state that endures to this day.

Hunter Thompson characterized the general mood among the opposition party watching the results roll in as “weeping chaos.” I’ve always felt that was an incredibly potent and telling depiction of the cloud of anxiety and fear hanging over that evening, even from a writer well known for his often eccentric imagery.

In 1972, Nixon benefitted from a stable economy, consistently strong polling and a general uncertainty about the fitness of his opponent he had helped to foment through election tampering, so in conventional terms his victory shouldn’t have been a shock. But his sheer dominance on election night painted a chilling portrait of the average voter and the level of vulgarity, corruption and wickedness they were willing to tolerate in order to preserve the status quo. It wasn’t the first time the public had been stunned by such a revelation about their fellow citizens’ dark desires and disinterests, and certainly wouldn’t be the last. It’s the kind of thing that might make you a little nervous if you were to run out of gas outside a little barbecue joint in Kingsland, Texas.

The common fear that Hooper capitalized on in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and again later in his career with Funhouse is largely the same fear and anxiety central to every major American election: It is the fear that the people living all around us aren’t at all what we think they are, and are instead something far more extraordinary and perverse than we could ever imagine.

One of the standout scenes in Chainsaw is a moment early in the film, before any of the murders have begun, when the group of young hippies interact rather sheepishly with a group of locals outside the cemetery they’re visiting. A drunken older man lolls on his back, looking up almost directly into the sun overhead and muttering “Things happen hereabouts they don’t tell about. I see things” as the young people watch him with visible perturbance in their eyes. It’s one of the first signs that despite being Texans themselves they are clearly wading into a culture they don’t fully understand.

The older I get the more I feel as if I am living in the midst of a culture I don’t understand, and at the same time working quite hard to ensure that it never fully understands me either. I have a full time job where I am mostly polite to my coworkers, I keep a low profile on social media with regards to my political beliefs. In short, the things that happen hereabouts, I don’t tell about. And if that’s the way I act, I can hardly expect that the people around me, some of them even less comfortable openly discussing politics and culture than I am, are being entirely truthful about who they are on the inside.

While elections certainly can’t be expected to bear out all these hidden truths, they still uncover some of the aspects of our culture that otherwise live well below the surface. And it’s not just the outcomes of votes themselves, but the ideas and feelings that they embolden. These days, I find myself meeting each new election with an even mix of fear and morbid curiosity.

It’s become somewhat memetic for viewers to criticize the teens in horror films who wander carelessly into spooky abandoned houses. But to be honest, I understand their perspective. It can be obvious to me sometimes that whatever I’m approaching is likely to be awful, possibly unthinkable, but that doesn’t mean I can live comfortably without ever opening myself to hurt in exchange for knowing the full scope of it. In that spirit, there are few things that feel more like hurling yourself at the mercy of potentially cruel strangers than voting does, but I believe in it all the same.