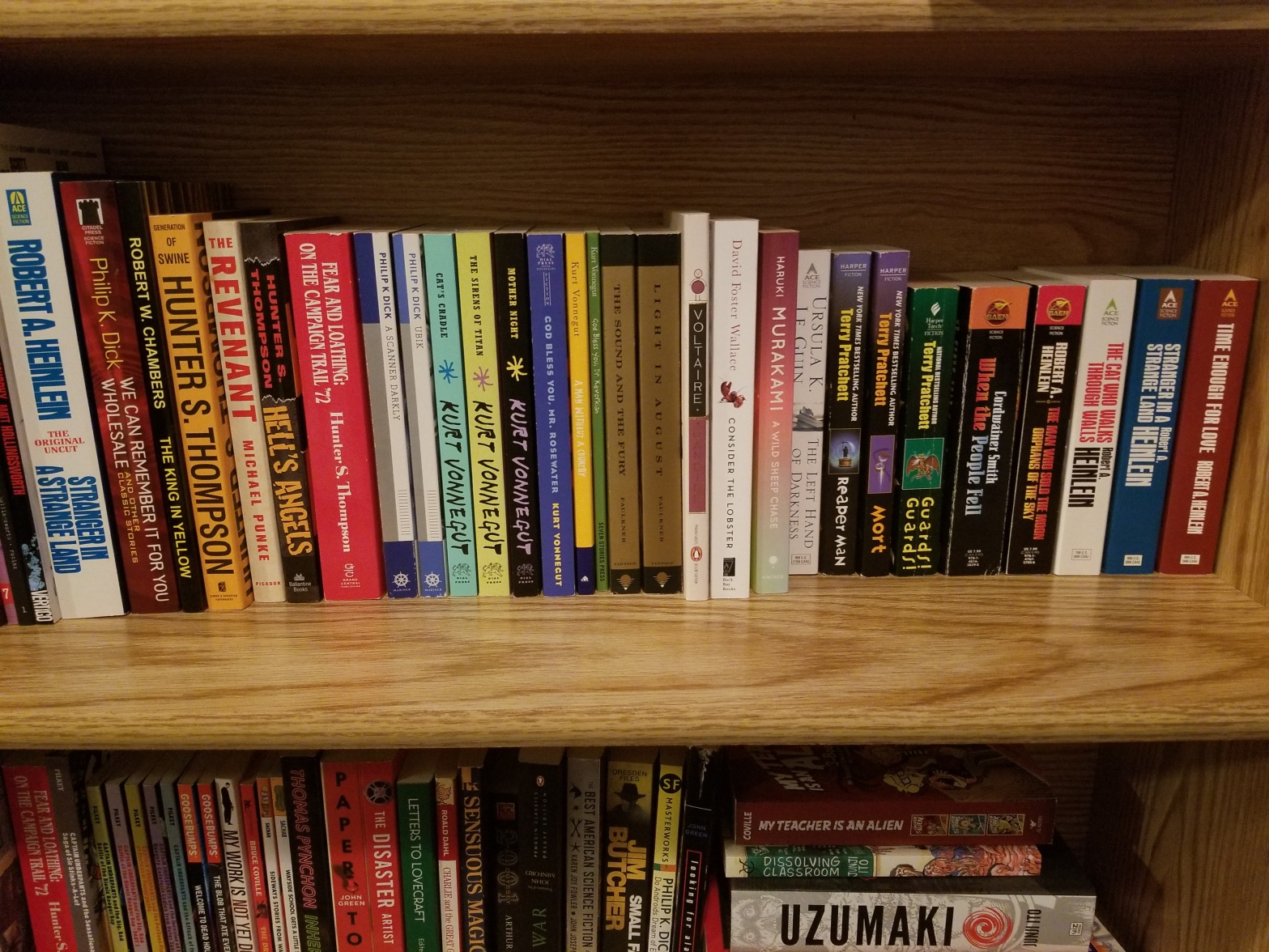

I’ve been watching the wonderful Philip K Dick inspired cyber dystopian Anime “Psycho Pass” lately and it is a rare and entirely welcome delight in these strange times. PKD is like a significantly less shitty Lovecraft in that his stories and concepts are adapted regularly and often with a great deal of care and ingenuity. But “Psycho Pass” is one of the best that I’ve seen in that it not only employs the concepts it borrows from “The Minority Report” to great effect, but also captures some of the intangible properties of Dick’s storytelling.

His stories tend to steadily depart from their inciting action as they unfold in a way that has rarely been replicated in even the most faithful adaptations. They pose interesting questions and then, rather than providing answers, the parameters of the story shift until the questions themselves no longer matter.

As the narrative runs its course, the characters somehow lose the plot entirely and fall slowly, surely, perilously away from their original motivations and into a sort of paranoid miasma. They leave the central thrust of the story, and conventional reality itself, behind as they go.

“Psycho Pass” brings a similar energy as the leads’ identity crises and internal struggles are almost as integral to the plot as the grisly murder mysteries and strange revelations that drive each episode.

It’s a dystopia that feels uniquely tailored to the moment as our recent collective struggles have drawn many of our personal narratives into a muddled series of recursions and entanglements.

Or maybe I’m trying to shoehorn Philip K Dick’s distinct style of speculation into our current reality because all the other classic dystopian fictions have had their turn.

With very little effort I could find essays and think pieces published over the last few years that compare modern culture and politics to “1984,” “A Handmaid’s Tale,” “A Brave New World” or “Fahrenheit 451.”

We’ve spent decades applying these old stories to new political and social developments. That’s why the covers and dust jackets of every commercial copy of classic dystopian fiction books are adorned with a pull quote to the tune of “Orwell’s cautionary tale endures to this day” or “Huxley’s chilling fable remains relevant years after its publication,” or “People! Are Still Reading! A Handmaid’s Tale! Whoa!!”

It’s fitting that we discuss these stories with a reverence we typically save for our oldest relatives. Because most of them are over half a century old. If “1984” were a person it would be eligible to collect Social Security payments.

Of course these stories are by no means toothless just because they’re old. But it’s also fairly easy to see that part of the reason they are referenced so often is that after enduring for decades as the standard for challenging and controversial narratives, they’ve finally become familiar. “A Handmaid’s Tale” was the subject of dozens of book banning and censorship battles throughout the 90’s. Now it’s a Hulu Original Series and you can download the Clare Danes narrated audiobook and listen to it on any platform you choose.

Sarah Urist Green said “Imagining the future is a kind of nostalgia” and I think by extension revisiting someone else’s imagined future over and over again is nostalgia of yet another kind.

At least that’s true if speculative fiction is actually about the future.

One of the reasons that we are prone to feeling as if we are living in a dystopia and that each new development is a step along that path is that, as Ursula LeGuin points out, “Science Fiction is not predictive, it is descriptive.”

George Orwell started composing “1984” in 1947, two years after the fall of modern history’s most infamous authoritarian regime. Its themes spin at least partially out of his anxieties over the restructuring of global politics following the second world war. It reads to us as a warning for the future, but it is very much a treatise challenging the governmental excesses of Orwell’s present.

Most of these famous dystopian novels are set in the future, but truthfully they’re about the past. The present for the people who wrote them. Imagining these futures isn’t a new sort of nostalgia. It’s the old, comforting, familiar kind.

Casting ongoing concerns in our culture as Orwellian or Huxleyian is a way of binding an uncertain and often terrifying series of events to a more stable and digestible framework.

We compare Covid-19 to the Spanish Flu for similar reasons. Even though the Spanish Flu killed millions and was genuinely a harrowing, bone chilling experience to live through there is still a level of comfort in the bare notion that we did live through it. The comparison allows us to believe we’ve been through this before, and survived. Even though we haven’t been through it before, and haven’t survived.

Someday, hopefully, we may be able to look back and apply our current troubles to whatever new, seemingly labyrinthine problem we’re facing. Because surviving these troubles and letting time do what it does best will eventually render them toothless, ineffectual, and, in a sense, comforting.

But who am I to say one way or another?

After all, I just write articles every week comparing old fiction to things that have happened to me lately.